Edward Hopper’s New York: The Exhibition

Organized in thematic chapters spanning Hopper’s entire career, the installation comprises eight sections including four expansive gallery spaces showcasing many of Hopper’s most celebrated paintings and four pavilions that focus on key topics through dynamic groupings of paintings, works on paper, and archival materials, many of which have rarely been exhibited to the public.

Edward Hopper’s New York begins with early sketches and paintings from the artist’s first years traveling into and around the city, from 1899 to 1915, as he grew from a commuting art student to a Greenwich Village resident. In Moving Train (c. 1900), Tugboat with Black Smokestack (1908), and El Station (1908) he observed the ways people occupied and moved through space within a dramatically developing urban environment.

Although Hopper aspired to recognition as a painter, his first successes came in print through his illustrations and etchings, an important history featured in a section of the exhibition titled “The City in Print.” His artworks for illustrations and published commissions for magazines and advertisements often featured urban motifs inspired by New York—theaters, restaurants, offices, and city dwellers—that would become foundational to his art. During this early period, he also consolidated many of his impressions of New York through etchings like East Side Interior (1922) and The Open Window (c. 1918–19), which preview the dramatic use of light that has become synonymous with Hopper’s work.

“The Window,” the next section, focuses on this enduring motif for Hopper—one that he explored with great interest in his city scenes. While strolling New York’s streets and riding its elevated trains, Hopper was particularly drawn to the fluid boundaries between public and private space in a city where all aspects of everyday life—from goods in a storefront display to unguarded moments in a café—are equally exposed. In paintings on view such as Automat (1927), Night Windows (1928), and Room in Brooklyn (1932), Hopper imagines the unlimited compositional and narrative possibilities of the city’s windowed facades, the potential for looking and being looked at, and the discomfiting awareness of being alone in a crowd.

Edward Hopper’s New York presents, for the first time together, the artist's panoramic cityscapes, installed as a group in a section of the exhibition titled “The Horizontal City.” Early Sunday Morning (1930), Manhattan Bridge Loop (1928), Blackwell’s Island (1928), Apartment Houses, East River (c. 1930), and Macomb’s Dam Bridge (1935), five paintings made between 1928 and 1935, all share nearly identical dimensions and format. Seen together, they offer invaluable insight into Hopper’s contrarian vision of the growing city at a time when New York was increasingly defined by its relentless skyward development.

“Washington Square” highlights the importance of Hopper’s neighborhood as his home and muse for nearly 55 years. Paintings like City Roofs (1932) and November, Washington Square (1932/1959) show Hopper’s fascination with the city views visible from his windows and his rooftop, and a rare series of watercolors—a practice he generally reserved for his travels to New England and elsewhere—reveals how attuned he was to the spatial dynamics and subtleties of the city’s built environment. As documented in the exhibited correspondence and notebooks, the Hoppers were fierce advocates of Washington Square, and they argued tirelessly for the preservation of their neighborhood as a haven for artists and as one of the city’s cultural landmarks.

“Theater,” a particularly revealing gallery in the exhibition, explores Hopper’s passion for the stage and the critical role it played as an active mode of spectatorship and source of visual inspiration. This section includes archival items like the Hoppers’ preserved ticket stubs and theatergoing notebooks and highlights the ways that theater spaces and set design influenced Hopper’s compositions through works like Two on the Aisle (1927) and The Sheridan Theatre (1937). Additionally, the presentation of New York Movie (1939) and a group of its preparatory studies along with figural sketches for other paintings reveal the Hoppers’ collaborative scene staging, in which Jo played an active part as model.

Throughout his career, Hopper explored the city with sketchbook in hand, recording his observations through drawing, a practice highlighted in this section of the exhibition. A large selection of his sketches and preparatory studies on view in “Sketching New York” chart Hopper’s favored locations across the city, many of which the artist returned to again and again in order to capture different impressions that he could later explore on canvas.

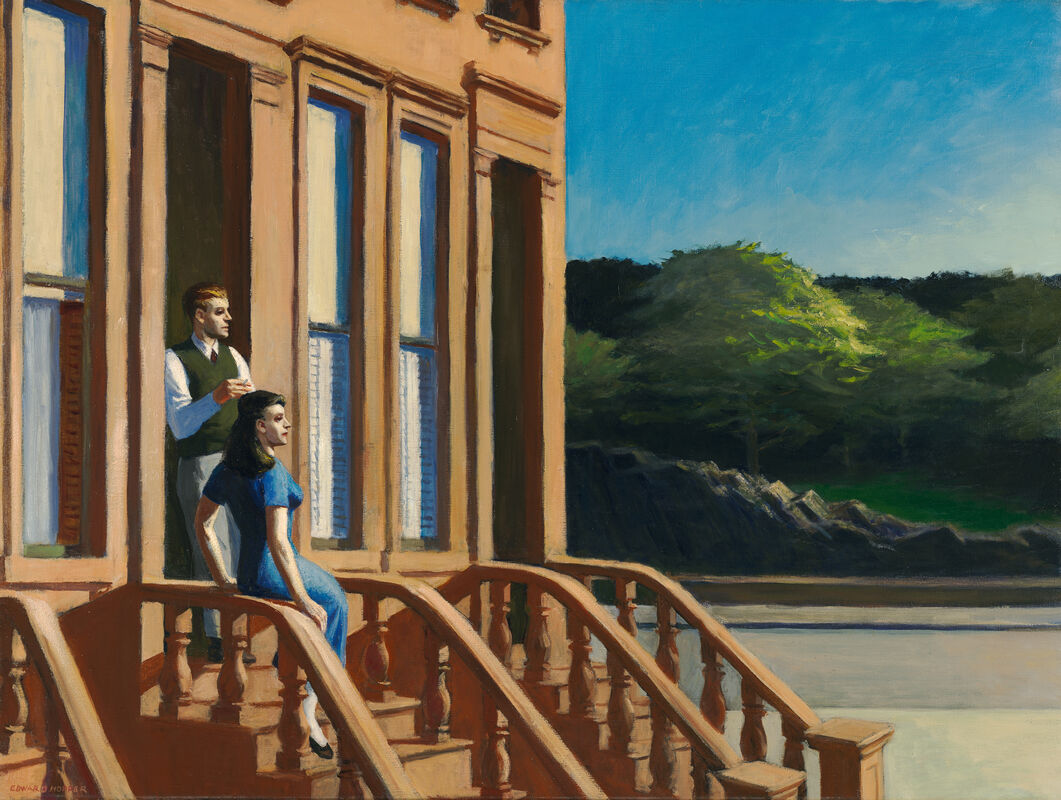

Finally, in “Reality and Fantasy,” a group of ambitious late paintings, characterized by radically simplified geometry and uncanny, dreamlike settings, reveal how New York increasingly served as a stage set or backdrop for Hopper’s evocative distillations of urban experience. In works such as Morning in a City (1944), Sunlight on Brownstones (1956), and Sunlight in a Cafeteria (1958), Hopper created compositions that depart from specific sites while still tapping into urban sensations, reflecting his desire, as noted in his personal journal “Notes on Painting”, to create a “realistic art from which fantasy can grow.”

For more information about the artworks included in this exhibition, please see Conaty’s catalogue essay Approaching a City: Hopper and New York.

|

Comments

Post a Comment